| Classwise Concept with Examples | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th |

Chapter 1 Sets (Concepts)

Embark on a journey into the fundamental language of modern mathematics with this introductory chapter on Sets. The concept of a set, while seemingly simple, provides the foundational bedrock upon which vast areas of mathematics, including logic, probability, algebra, and topology, are built. A set is rigorously defined as a well-defined collection of distinct objects. The term "well-defined" is crucial – it means we must be able to determine definitively whether any given object belongs to the collection or not. These objects within the set are referred to as its elements or members.

We explore two primary methods for representing sets:

- Roster Form (or Tabular Form): This method involves explicitly listing all the elements of the set, separated by commas and enclosed within curly braces $\{ \}$. For example, the set of the first three natural numbers is represented as $\{1, 2, 3\}$. The order in which elements are listed is immaterial.

- Set-Builder Form: This method describes the elements of the set based on a common property they all share, rather than listing them individually. It uses the format `{x | P(x)}` or `{x : P(x)}`, which reads as "the set of all elements $x$ such that $x$ satisfies the property $P(x)$". For instance, the same set $\{1, 2, 3\}$ can be written in set-builder form as $\{x | x \text{ is a natural number and } x < 4\}$.

Understanding different types of sets is essential:

- The Empty Set (or Null Set): Denoted by $\emptyset$ or `{ }`, this special set contains no elements whatsoever.

- Finite Sets: Sets containing a definite, countable number of elements.

- Infinite Sets: Sets whose elements cannot be counted; they continue indefinitely (e.g., the set of all natural numbers).

- Singleton Set: A set containing exactly one element (e.g., $\{5\}$).

- Equal Sets: Two sets A and B are equal ($A=B$) if and only if they have the exact same elements.

- Equivalent Sets: Two finite sets are equivalent if they have the same number of elements, known as their cardinality (denoted $n(A)$ for set A). Equal sets are always equivalent, but equivalent sets are not necessarily equal.

The concept of a Subset (denoted by $\subseteq$) is fundamental. Set A is a subset of set B ($A \subseteq B$) if every element of A is also present in B. If A is a subset of B and $A \neq B$, then A is a proper subset of B (denoted by $\subset$). The Power Set of a set A, denoted by $P(A)$, is the set containing all possible subsets of A (including the empty set and the set A itself). If a finite set A has $m$ elements ($n(A) = m$), then its power set $P(A)$ has $2^m$ elements ($n(P(A)) = 2^m$). We also define the Universal Set (usually denoted by $U$), which represents the encompassing set of all elements relevant to a particular discussion or problem context.

Venn diagrams are introduced as powerful visual tools. These diagrams typically use overlapping circles within a rectangle (representing the universal set $U$) to illustrate the relationships and interactions between different sets visually.

We then define the major operations that can be performed on sets:

- Union ($A \cup B$): The set of all elements that are in set A, or in set B, or in both.

- Intersection ($A \cap B$): The set of all elements that are common to both set A and set B.

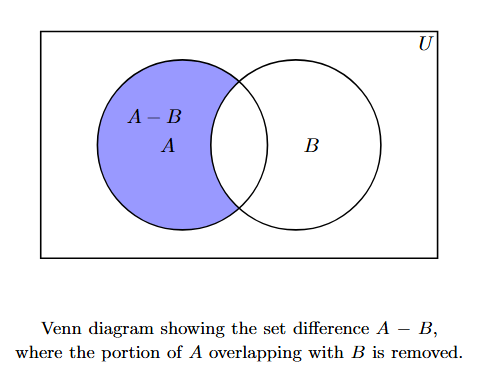

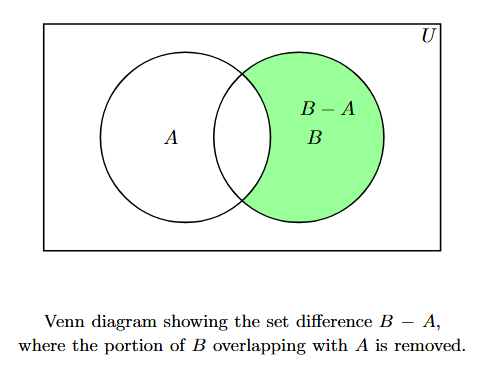

- Difference ($A - B$): The set of all elements that are in set A but not in set B.

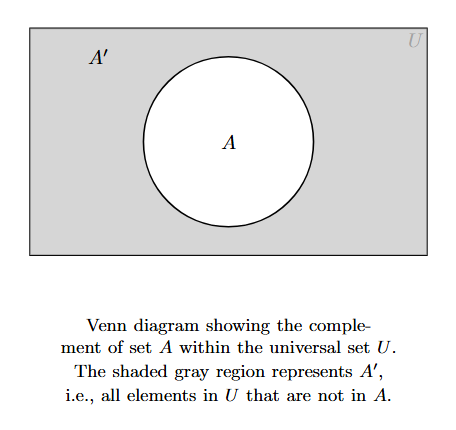

- Complement ($A'$ or $A^c$): The set of all elements in the universal set $U$ that are not in set A ($A' = U - A$).

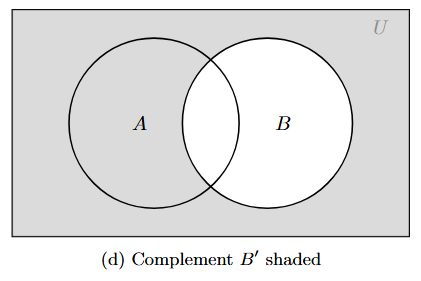

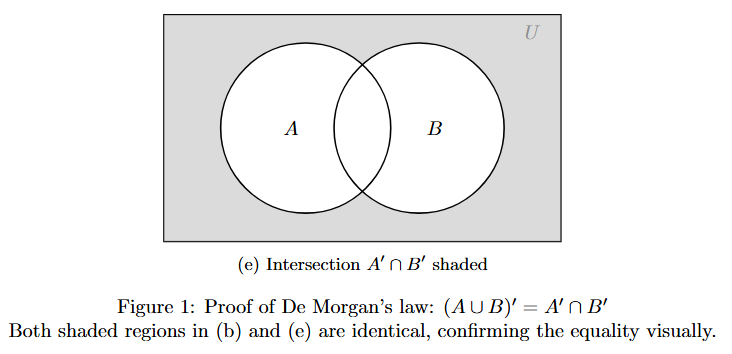

Important properties governing these operations are explored, often illustrated with Venn diagrams. These include commutative laws ($A \cup B = B \cup A$; $A \cap B = B \cap A$), associative laws ($(A \cup B) \cup C = A \cup (B \cup C)$; $(A \cap B) \cap C = A \cap (B \cap C)$), distributive laws ($A \cup (B \cap C) = (A \cup B) \cap (A \cup C)$ and $A \cap (B \cup C) = (A \cap B) \cup (A \cap C)$), identity laws involving $\emptyset$ and $U$, complement laws ($A \cup A' = U$, $A \cap A' = \emptyset$), and the crucial De Morgan's Laws: $(A \cup B)' = A' \cap B'$ and $(A \cap B)' = A' \cup B'$.

Finally, the chapter culminates in applying these concepts to solve practical problems, often involving analyzing survey data or scenarios described using set language. This frequently utilizes cardinality formulas, most notably the principle of inclusion-exclusion for two sets: $\mathbf{n(A \cup B) = n(A) + n(B) - n(A \cap B)}$, and its extension for three sets, allowing us to calculate the number of elements in various unions and intersections based on given information.

Basic of Sets

In mathematics, a set is a collection of objects that is both well-defined and contains distinct elements. The objects that make up a set are called its elements or members.

Let's break down the key characteristics that properly define a set.

Key Characteristics of a Set

For a collection of objects to be considered a mathematical set, it must satisfy the following fundamental properties:

1. Well-Defined Collection

The term "well-defined" is the most crucial aspect of a set. It means that for any given object, there must be a clear and unambiguous rule or criterion that allows us to decide with certainty whether that object belongs to the collection or not. There should be no room for opinion or subjective judgment.

- Criterion: A collection is well-defined if its description is objective and universally understood.

- Ambiguity: If a collection's description depends on subjective terms like "good," "beautiful," "talented," or "difficult," it is not well-defined and therefore cannot be a set.

2. Distinct Elements

Every element in a set must be unique. If an object is listed more than once when describing a set, it is only counted as a single element. Repetition of elements is ignored.

- Example: Consider the collection of letters in the word "SUCCESS". The distinct letters are S, U, C, E. Therefore, the set of letters in this word is written as $\{S, U, C, E\}$. The repeated 'S' and 'C' are included only once.

3. Order is Immaterial

The order in which the elements of a set are listed does not matter. As long as two sets contain the exact same elements, they are considered identical, regardless of the arrangement of those elements.

- Example: The set $\{a, b, c\}$ is exactly the same as the set $\{c, a, b\}$ and the set $\{b, c, a\}$. All three notations represent the same collection of elements.

Examples of Well-defined Collections (Sets):

Let's look at some examples of collections that are considered sets:

1. The collection of all vowels in the English alphabet.

This collection consists of the letters $\{a, e, i, o, u\}$. For any given letter, we can definitively say whether it is one of these five letters or not. Therefore, this collection is well-defined and is a set.

2. The collection of all natural numbers less than 10.

The natural numbers are $\{1, 2, 3, ...\}$. The collection of natural numbers less than 10 is $\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9\}$. For any number, we can check if it is a natural number and if it is less than 10. This is a well-defined collection and thus a set.

3. The collection of all rivers in India.

While large, this collection is still well-defined. There are clear geographical criteria for what constitutes a river, and political boundaries define whether a river is in India. For any given body of water, experts can determine if it is a river in India. Therefore, this collection is a set.

Examples of Collections that are Not Well-defined (Not Sets):

Now let's consider some collections that are not sets:

1. The collection of all beautiful flowers in a garden.

The word "beautiful" is subjective. What one person considers beautiful, another might not. There is no universal criterion for beauty. Thus, it is impossible to definitively determine whether a particular flower belongs to this collection. This collection is not well-defined and therefore not a set.

2. The collection of talented cricketers of India.

The term "talented" is subjective and depends on personal opinion or varying criteria (e.g., batting average, bowling figures, fielding skills, leadership). A collection based on subjective criteria like talent is not well-defined.

3. The collection of good students in a class.

"Good" can be interpreted in many ways – academically good, well-behaved, helpful, etc. Without a specific, measurable criterion, it is impossible to objectively determine who is a "good" student. This collection is not well-defined.

Notation for Sets and Elements:

To represent sets and their elements mathematically, we use specific notation:

Sets are usually denoted by capital letters such as $A, B, C, X, Y, Z$, etc.

The elements or members of a set are usually denoted by lowercase letters such as $a, b, c, x, y, z$, etc.

When we want to state that an element $a$ belongs to a set $A$, we use the symbol '$\in$'. We write this as $a \in A$. The symbol '$\in$' is read as "belongs to", "is an element of", or "is a member of".

If an object $b$ does not belong to a set $A$, we use the symbol '$\notin$'. We write this as $b \notin A$. The symbol '$\notin$' is read as "does not belong to" or "is not an element of".

Example 1. Consider the set $A = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$. Check if 3 and 6 belong to set A.

Answer:

To check if an element belongs to a set, we look for its presence among the members listed within the curly braces $\{\}$.

In the given set $A = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$, the number 3 is clearly listed as one of the elements.

So, we can say that 3 belongs to set $A$. Using mathematical notation, we write:

$3 \in A$

Now, let's check for the number 6. Looking at the elements of set $A$ which are $\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$, the number 6 is not present in this list.

So, we can say that 6 does not belong to set $A$. Using mathematical notation, we write:

$6 \notin A$

Representations of a Set

Every set can be described or represented in two main ways. These methods provide different perspectives on how to list or define the elements that constitute a set. The two principal ways of representing a set are:

1. Roster or Tabular form

2. Set-builder form

1. Roster or Tabular Form:

In the Roster form, also known as the Tabular form, we represent a set by listing all its elements explicitly. The elements are separated by commas, and the entire list is enclosed within curly braces $\{\}$. This method is straightforward when the number of elements is finite and not too large.

Examples of Sets in Roster Form:

Here are a few illustrations of sets written in Roster form:

1. The set of all vowels in the English alphabet.

This set is represented as $\{a, e, i, o, u\}$.

2. The set of all even natural numbers less than 10.

The even natural numbers are $2, 4, 6, 8, 10, ...$. Those less than 10 are $2, 4, 6, 8$. So the set is $\{2, 4, 6, 8\}$.

3. The set of roots of the quadratic equation $x^2 - 5x + 6 = 0$.

To find the roots, we factor the quadratic equation: $(x-2)(x-3) = 0$. The roots are $x=2$ and $x=3$. Thus, the set of roots is $\{2, 3\}$.

Important points about Roster form

When writing sets in Roster form, remember these key rules:

(i) Order of elements does not matter

- The arrangement of elements within the curly braces does not change the set.

- For example, the set $\{1, 2, 3\}$ is exactly the same as the set $\{3, 1, 2\}$ and $\{2, 1, 3\}$.

(ii) Elements are not repeated

- Each distinct element should be listed only once.

- Repetitions of elements are ignored.

- For example, the set of letters in the word 'SCHOOL' is $\{S, C, H, O, L\}$.

- The element 'O' is listed only once, even though it appears twice in the word.

(iii) Use of ellipsis (...) for large or infinite sets

- For sets with too many elements to list, an ellipsis (...) is used to show that the established pattern continues.

- This is essential for representing infinite sets.

- Example (Natural Numbers): The set $\mathbb{N}$ is written as $\{1, 2, 3, ...\}$.

- Example (Integers): The set $\mathbb{Z}$ is written as $\{..., -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, ...\}$.

2. Set-Builder Form

The Set-builder form is a method of describing a set by stating a property that its elements must satisfy.

- It defines a set by a common rule or a characteristic property.

- Every element in the set must possess this property.

- No element outside the set should possess this property.

- This form is particularly useful for representing large or infinite sets where listing all elements in roster form is impractical or impossible.

Structure and Reading

The general structure for the set-builder form is:

$\{x : P(x)\}$ or $\{x | P(x)\}$

This notation is broken down as follows:

- $\{...\}$: "The set of..."

- $x$: "...all elements $x$..." (Here, $x$ is a variable representing any element in the set).

- $:$ or $|$: "...such that..."

- $P(x)$: "...the property $P(x)$ is true." ($P(x)$ is the rule or condition that $x$ must satisfy).

So, $\{x : P(x)\}$ is read as: "The set of all elements $x$ such that $x$ satisfies the property $P(x)$".

Examples of Sets in Set-Builder Form

Let's convert some sets from roster form to set-builder form.

1. Roster Form: $V = \{a, e, i, o, u\}$

Set-Builder Form: $V = \{x : x \text{ is a vowel in the English alphabet}\}$.

2. Roster Form: $A = \{2, 4, 6, 8\}$

Set-Builder Form: $A = \{x : x \text{ is an even natural number and } x < 10\}$.

3. Roster Form (for Natural Numbers): $\mathbb{N} = \{1, 2, 3, ...\}$

Set-Builder Form: $\mathbb{N} = \{x : x \text{ is a natural number}\}$.

4. The set of Rational Numbers ($\mathbb{Q}$)

A rational number is any number that can be written as a fraction $\frac{p}{q}$, where $p$ and $q$ are integers and $q \neq 0$.

Set-Builder Form: $\mathbb{Q} = \{x : x = \frac{p}{q}, \text{ where } p, q \in \mathbb{Z} \text{ and } q \neq 0\}$.

Example 1. Write the set $A = \{x : x \text{ is an integer and } -3 < x < 5\}$ in roster form.

Answer:

The set $A$ is defined in Set-builder form as the set of all integers $x$ such that $x$ is greater than -3 and less than 5. We need to list all integers that satisfy the condition $-3 < x < 5$.

The integers greater than -3 are -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, ...

The integers less than 5 are ..., 0, 1, 2, 3, 4.

The integers that are *both* greater than -3 *and* less than 5 are the numbers that appear in both lists. These are -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4.

Therefore, in roster form, the set $A$ is represented by listing these elements within curly braces, separated by commas:

$A = \{-2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4\}$

Example 2. Write the set $B = \{1, 4, 9, 16, 25, ...\}$ in set-builder form.

Answer:

The set $B$ is given in roster form as $\{1, 4, 9, 16, 25, ...\}$. We need to identify a common property that is shared by all these elements and by no other elements not in the set. Let's look at the elements: $1 = 1^2$ $4 = 2^2$ $9 = 3^2$ $16 = 4^2$ $25 = 5^2$ The pattern observed is that each element is the square of a natural number. The ellipsis (...) indicates that this pattern continues infinitely for all natural numbers.

So, the property $P(x)$ for an element $x$ to be in set $B$ is that $x$ must be the square of a natural number $n$. We can write this property as $x = n^2$, where $n$ is a natural number ($n \in \mathbb{N}$).

Therefore, in set-builder form, the set $B$ is written as:

$B = \{x : x = n^2, \text{ where } n \in \mathbb{N}\}$

Alternatively, we could write it using the variable $n$ directly:

$B = \{n^2 : n \in \mathbb{N}\}$

Both forms express the same set.

Kinds of Sets

Sets can be categorized into different types based on the nature and number of elements they contain. Understanding these different types is fundamental to working with sets in mathematics. Based on the number of elements they contain or their properties, sets are broadly classified into the following types:

1. Empty Set (Null Set or Void Set):

An Empty Set is a set that contains absolutely no elements. It is the set with zero elements. Due to having no elements, it is also referred to as the Null Set or Void Set.

The empty set is denoted by the symbol $\emptyset$ (phi) or simply by empty curly braces $ \left \{ \right \} $.

Examples of Empty Sets:

Let's consider some examples of collections that form an empty set:

1. The set of all natural numbers less than 1.

Natural numbers are $\{1, 2, 3, ...\}$. There is no natural number that is strictly less than 1. Therefore, the set of all natural numbers less than 1 contains no elements and is the empty set, denoted as $\emptyset$ or $ \left \{ \right \} $.

2. The set of real roots of the equation $x^2 + 1 = 0$.

To find the roots, we solve the equation $x^2 = -1$. In the system of real numbers ($\mathbb{R}$), the square of any real number is always non-negative ($x^2 \geq 0$). There is no real number whose square is -1. Thus, the set of real roots for this equation is the empty set, $\emptyset$. (Note: This equation does have complex roots, but we are looking for real roots).

3. The set of students currently studying in both Class 10 and Class 11 in the same school simultaneously.

According to standard educational rules, a student is enrolled in only one class at a time within a single school. Therefore, there cannot be a student who is simultaneously in both Class 10 and Class 11. This collection is empty, representing the empty set $\emptyset$.

2. Finite Set:

A set is called a Finite Set if it is either the empty set or if its elements can be counted completely, meaning it consists of a definite, non-negative integer number of elements. The process of counting the elements must terminate.

Examples of Finite Sets:

1. The set of days in a week.

This set is $\{$Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday$\}$. It has exactly 7 elements, which is a definite number. Thus, it is a finite set.

2. The set of students in your school.

Although the number might be large, it is a fixed, countable number. So, this is a finite set.

3. The set $\{1, 2, 3, ..., 100\}$.

This set consists of all natural numbers from 1 to 100. It has exactly 100 elements. This is a definite number, so the set is finite.

It's important to remember that the empty set $\emptyset$ is also considered a finite set because it has 0 elements, and 0 is a definite number.

3. Infinite Set:

A set that is not finite is called an Infinite Set. The elements of an infinite set cannot be listed or counted completely in a definite manner because the counting process would never terminate.

Examples of Infinite Sets:

1. The set of all natural numbers.

$\mathbb{N} = \{1, 2, 3, ...\}$. The list of natural numbers goes on forever, so this set is infinite.

2. The set of all integers.

$\mathbb{Z} = \{..., -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...\}$. This set extends infinitely in both positive and negative directions, so it is infinite.

3. The set of all points on a line.

Between any two distinct points on a line, there are infinitely many other points. This implies that the total number of points on a line cannot be counted, making it an infinite set.

4. The set of all real numbers.

$\mathbb{R}$. The set of real numbers includes all rational and irrational numbers. Like the points on a line, there are infinitely many real numbers, and they cannot be listed in a sequence, so this set is infinite.

Note:

While representing some infinite sets in roster form, we use dots (...) to indicate that the list continues indefinitely following the established pattern (e.g., $\{1, 2, 3, ...\}$). However, not all infinite sets can be represented in roster form. For example, the set of real numbers $\mathbb{R}$ cannot be listed element by element, even with dots, because the numbers are not countable in a sequential manner like integers or natural numbers.

4. Equal Sets:

Two sets, say $A$ and $B$, are said to be Equal Sets if and only if they contain precisely the same elements. This means that every element belonging to set $A$ must also belong to set $B$, and conversely, every element belonging to set $B$ must also belong to set $A$.

If sets $A$ and $B$ are equal, we write $A = B$. If they do not contain exactly the same elements, they are said to be unequal, and we write $A \neq B$.

It's important to recall from the representation of sets that the order in which elements are listed in the roster form does not affect the set. Also, repetition of elements is not considered. These points are crucial when checking for equality of sets.

Examples of Equal and Unequal Sets:

1. If $A = \{1, 2, 3, 4\}$ and $B = \{3, 1, 4, 2\}$.

Set $A$ contains elements 1, 2, 3, and 4. Set $B$ contains elements 3, 1, 4, and 2. The elements are exactly the same, just listed in a different order. Therefore, $A = B$.

2. If $A = \{x : x \text{ is a letter in the word 'READ'}\}$ and $B = \{x : x \text{ is a letter in the word 'DEAR'}\}$.

In roster form, set $A = \{R, E, A, D\}$ (distinct letters from 'READ'). In roster form, set $B = \{D, E, A, R\}$ (distinct letters from 'DEAR'). The elements in both sets are R, E, A, D. Since they have exactly the same elements, $A = B$.

3. If $A = \{1, 2, 3\}$ and $B = \{1, 2, 4\}$.

Set $A$ contains the element 3, but 3 is not in set $B$. Set $B$ contains the element 4, but 4 is not in set $A$. Since they do not have exactly the same elements, $A \neq B$.

5. Equivalent Sets:

Two finite sets $A$ and $B$ are said to be Equivalent Sets if they have the same number of elements. In other words, two finite sets are equivalent if their cardinal numbers are equal.

We denote the cardinal number of a set $A$ (the number of distinct elements in a finite set $A$) as $n(A)$. Two finite sets $A$ and $B$ are equivalent if $n(A) = n(B)$.

Equivalence of sets is sometimes denoted by $A \sim B$ or $A \approx B$.

Examples of Equivalent Sets:

1. If $A = \{1, 2, 3\}$ and $B = \{a, b, c\}$.

The number of elements in set $A$ is $n(A) = 3$. The number of elements in set $B$ is $n(B) = 3$. Since $n(A) = n(B)$, sets $A$ and $B$ are equivalent $(A \sim B)$. Note that $A$ and $B$ are not equal $(A \neq B)$ as they have different elements.

2. If $A = \{1, 2, 3, 4\}$ and $B = \{1, 3, 5, 7\}$.

The number of elements in set $A$ is $n(A) = 4$. The number of elements in set $B$ is $n(B) = 4$. Since $n(A) = n(B)$, sets $A$ and $B$ are equivalent $(A \sim B)$. Again, $A \neq B$ as the elements are different.

Note:

There is a relationship between equal sets and equivalent sets:

- Every pair of equal sets is equivalent. If $A = B$, they have exactly the same elements, so they must have the same number of elements, i.e., $n(A) = n(B)$. Thus, equal sets are always equivalent.

- However, every pair of equivalent sets is not necessarily equal. Equivalent sets only need to have the same number of elements; the elements themselves can be different (unless the set is empty, in which case both equal and equivalent sets must be $\emptyset$).

6. Singleton Set:

A set that contains exactly one element is called a Singleton Set or a unit set.

Examples of Singleton Sets:

1. $\{5\}$ is a singleton set because it contains only the number 5.

2. $\{x : x \text{ is an even prime number}\}$.

A prime number is a natural number greater than 1 that has no positive divisors other than 1 and itself. The set of prime numbers is $\{2, 3, 5, 7, 11, ...\}$. Among these, the only number that is even is 2. So, the set of even prime numbers contains only the element 2. Thus, the set is $\{2\}$, which is a singleton set.

3. $\{x : x \in \mathbb{Z} \text{ and } x^2 = 0\}$.

We are looking for integers $x$ that satisfy the equation $x^2 = 0$. The only integer whose square is 0 is 0 itself. So, the set of integers satisfying this condition is $\{0\}$, which is a singleton set.

Cardinal Number of a Finite Set

For a finite set, the cardinal number (or cardinality) is a measure of the number of distinct elements it contains. It tells us "how many" elements are in the set.

If $A$ is a finite set, the cardinal number of $A$ is typically denoted by $n(A)$ or sometimes by $|A|$. The symbol $n(A)$ reads as "the number of elements in set A" or "the cardinality of set A".

Recall that a finite set is one that is either empty or whose elements can be counted completely, resulting in a non-negative integer.

Examples:

Let's find the cardinal number for the following finite sets:

1. If $A = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$.

This set contains the distinct elements 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Counting these elements, we find there are 5 of them. Therefore, the cardinal number of set $A$ is 5.

$n(A) = 5$

2. If $B = \{a, b, c, d\}$.

This set contains the distinct elements a, b, c, and d. There are 4 distinct elements. Thus, the cardinal number of set $B$ is 4.

$n(B) = 4$

3. If $C = \{x : x \text{ is a letter in the word 'ASSASSINATION'}\}$.

First, we need to list the distinct letters present in the word 'ASSASSINATION'. The letters are A, S, I, N, T, O. Note that some letters like 'A', 'S', 'I', and 'N' appear multiple times, but when forming a set, we only list distinct elements.

So, the set $C$ in roster form is $C = \{A, S, I, N, T, O\}$.

Now, we count the distinct elements in set $C$. There are 6 distinct elements.

Therefore, the cardinal number of set $C$ is 6.

$n(C) = 6$

4. If $D = \emptyset$, the empty set.

The empty set contains no elements. The number of elements in the empty set is 0. Therefore, the cardinal number of the empty set is 0.

$n(\emptyset) = 0$

5. If $E = \{ \{1, 2\}, 3 \}$.

This set might look tricky. The elements of set $E$ are the items listed directly inside the outermost curly braces, separated by commas. The elements are the set $\{1, 2\}$ and the number 3. These are two distinct items.

So, set $E$ has two elements: one element is the set $\{1, 2\}$, and the other element is the number 3.

Therefore, the cardinal number of set $E$ is 2.

$n(E) = 2$

Note that the cardinal number of the set $\{1, 2\}$ itself is $n(\{1, 2\}) = 2$, but $\{1, 2\}$ is just one element within set $E$.

Note:

The concept of a cardinal number as a single, definite non-negative integer is applicable only to finite sets. Infinite sets, by definition, cannot have their elements counted completely in a finite manner. While there is a theory of cardinal numbers for infinite sets (involving concepts like countability), for the scope of introductory set theory at this level, when we refer to the "cardinal number" and use the notation $n(A)$ or $|A|$, we are generally referring to finite sets.

Standard Sets of Numbers

In mathematics, certain sets of numbers are so fundamental and frequently used that they are given special names and standard symbols. Understanding these sets and their relationships is crucial for studying various mathematical concepts. Here are some of the standard sets of numbers:

List of Standard Sets:

1. $\mathbb{N}$: The set of all Natural Numbers.

These are the numbers used for counting. Depending on the convention followed, 0 may or may not be included. However, in most Indian contexts and for Class 11 syllabus, natural numbers start from 1.

$\mathbb{N} = \{1, 2, 3, 4, ...\}$

2. $\mathbb{W}$: The set of all Whole Numbers.

This set includes all natural numbers along with zero.

$\mathbb{W} = \{0, 1, 2, 3, ...\}$

Note that $\mathbb{N} \subset \mathbb{W}$.

3. $\mathbb{Z}$: The set of all Integers.

This set includes all positive whole numbers, negative whole numbers, and zero.

$\mathbb{Z} = \{..., -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...\}$

Note that $\mathbb{W} \subset \mathbb{Z}$.

4. $\mathbb{Q}$: The set of all Rational Numbers.

A number is rational if it can be expressed in the form $\frac{p}{q}$, where $p$ and $q$ are integers, and $q$ is not equal to zero. These numbers, when expressed in decimal form, are either terminating or non-terminating repeating decimals.

$\mathbb{Q} = \{ \frac{p}{q} : p \in \mathbb{Z}, q \in \mathbb{Z}, q \neq 0 \}$

Every integer $z$ can be written as $\frac{z}{1}$, where $z \in \mathbb{Z}$ and $1 \neq 0$. Therefore, every integer is a rational number. Note that $\mathbb{Z} \subset \mathbb{Q}$.

5. $\mathbb{T}$ or $\mathbb{Q}^c$: The set of all Irrational Numbers.

These are the real numbers that are not rational. They cannot be expressed in the form $\frac{p}{q}$. When expressed in decimal form, they are non-terminating and non-repeating decimals.

Examples include $\sqrt{2}, \sqrt{3}, \pi$ (Pi), $e$ (Euler's number), etc.

$\mathbb{T} = \{x : x \in \mathbb{R} \text{ and } x \notin \mathbb{Q} \}$

6. $\mathbb{R}$: The set of all Real Numbers.

This set is the union of the set of rational numbers and the set of irrational numbers. Any number that can be plotted on the number line is a real number.

$\mathbb{R} = \mathbb{Q} \cup \mathbb{T}$

Note that $\mathbb{Q} \subset \mathbb{R}$ and $\mathbb{T} \subset \mathbb{R}$.

7. $\mathbb{C}$: The set of all Complex Numbers.

A complex number is a number that can be expressed in the form $a + bi$, where $a$ and $b$ are real numbers, and $i$ is the imaginary unit satisfying $i^2 = -1$ $(i = \sqrt{-1})$.

$\mathbb{C} = \{ a + bi : a \in \mathbb{R}, b \in \mathbb{R} \}$

Every real number $a$ can be written as $a + 0i$, which is a complex number with the imaginary part equal to zero. Therefore, every real number is a complex number. Note that $\mathbb{R} \subset \mathbb{C}$.

Standard Notations for Subsets of Number Sets:

We often use superscripts to denote specific subsets, such as positive or non-negative numbers:

- $\mathbb{Z}^+$: The set of all positive integers. $\mathbb{Z}^+ = \{1, 2, 3, ...\} = \mathbb{N}$.

- $\mathbb{Z}^-$: The set of all negative integers. $\mathbb{Z}^- = \{..., -3, -2, -1\}$.

- $\mathbb{Q}^+$: The set of all positive rational numbers.

- $\mathbb{Q}^-$: The set of all negative rational numbers.

- $\mathbb{R}^+$: The set of all positive real numbers.

- $\mathbb{R}^-$: The set of all negative real numbers.

Sometimes, $\mathbb{Z}_0^+$ or $\mathbb{Z}^{\geq 0}$ is used for non-negative integers $\{0, 1, 2, ...\}$ (which is equivalent to $\mathbb{W}$). Similarly, $\mathbb{Q}_0^+$ or $\mathbb{Q}^{\geq 0}$ and $\mathbb{R}_0^+$ or $\mathbb{R}^{\geq 0}$ denote non-negative rational and real numbers, respectively.

Relationship Between Standard Sets of Numbers:

These standard sets of numbers form a hierarchy, where each set is a subset of the next larger set. This means that every element of a smaller set is also an element of the larger set it is contained within.

The relationship can be summarized using the subset symbol ($\subset$):

$\mathbb{N} \subset \mathbb{W} \subset \mathbb{Z} \subset \mathbb{Q} \subset \mathbb{R} \subset \mathbb{C}$

In words, this means:

- Every Natural Number is a Whole Number.

- Every Whole Number is an Integer.

- Every Integer is a Rational Number.

- Every Rational Number is a Real Number.

- Every Real Number is a Complex Number.

Additionally, the set of irrational numbers ($\mathbb{T}$) is also a subset of the set of real numbers ($\mathbb{R}$), and the sets of rational and irrational numbers together form the set of real numbers, but they are disjoint (have no elements in common):

$\mathbb{T} \subset \mathbb{R}$

$\mathbb{Q} \cap \mathbb{T} = \emptyset$

$\mathbb{Q} \cup \mathbb{T} = \mathbb{R}$

Set Relations

Sets are not isolated entities; they can interact and be related to each other. Understanding these relationships is fundamental to set theory and its applications. Some of the important relations between sets include being a subset, a superset, the concept of a universal set, and the power set.

1. Subset

A set $A$ is called a subset of a set $B$ if every element of set $A$ is also an element of set $B$. In other words, set $A$ is contained within set $B$.

- The symbol for subset is $\subseteq$. We write $A \subseteq B$ to denote that $A$ is a subset of $B$.

- If there is at least one element in $A$ that is not in $B$, then $A$ is not a subset of $B$. We write this as $A \not\subseteq B$.

Symbolic Definition of Subset

Formally, the definition of a subset can be written using symbols as:

$A \subseteq B \iff (\forall x, x \in A \implies x \in B)$

This is read as: "$A$ is a subset of $B$ if and only if for all elements $x$, if $x$ is an element of $A$, then $x$ is also an element of $B$."

- $\forall$ stands for "for all".

- $\implies$ stands for "implies".

Examples of Subsets

1. Let $A = \{1, 2\}$ and $B = \{1, 2, 3\}$.

Since every element of $A$ (1 and 2) is also present in $B$, we can say that $A$ is a subset of $B$.

$A \subseteq B$

2. Let $P = \{a, b, c\}$ and $Q = \{a, b, d\}$.

Here, $c$ is in set $P$ but not in set $Q$. Therefore, $P$ is not a subset of $Q$.

$P \not\subseteq Q$

Similarly, $d$ is in set $Q$ but not in set $P$. Therefore, $Q$ is not a subset of $P$.

$Q \not\subseteq P$

3. Let $\mathbb{N}$ be the set of natural numbers and $\mathbb{Z}$ be the set of integers.

Since every natural number (1, 2, 3, ...) is also an integer, $\mathbb{N}$ is a subset of $\mathbb{Z}$.

$\mathbb{N} \subseteq \mathbb{Z}$

Properties of Subsets

(i) Every set is a subset of itself.

For any set $A$, it is always true that $A \subseteq A$. This is because every element in $A$ is, by definition, in $A$.

(ii) The empty set is a subset of every set.

For any set $A$, the empty set $\emptyset$ (a set with no elements) is always a subset: $\emptyset \subseteq A$.

This is because for $\emptyset \not\subseteq A$ to be true, there would have to be an element in $\emptyset$ that is not in $A$. Since $\emptyset$ has no elements, this is impossible. Thus, $\emptyset \subseteq A$ must be true.

(iii) Transitive Property of Subsets.

If set $A$ is a subset of set $B$, and set $B$ is a subset of set $C$, then $A$ must be a subset of $C$.

Symbolically: If $A \subseteq B$ and $B \subseteq C$, then $A \subseteq C$.

Proper Subset

If $A$ is a subset of $B$ ($A \subseteq B$) and $A$ is not equal to $B$ ($A \neq B$), then $A$ is called a proper subset of $B$.

- This means that all elements of $A$ are in $B$, and there is at least one element in $B$ that is not in $A$.

- The symbol for a proper subset is $\subset$ or $\subsetneq$. To avoid confusion, $\subsetneq$ is preferred.

Example: If $A = \{1, 2\}$ and $B = \{1, 2, 3\}$, then $A$ is a proper subset of $B$ because $A \subseteq B$ and $A \neq B$. We write $A \subsetneq B$.

Intervals as Subsets of $\mathbb{R}$

The set of real numbers, denoted by $\mathbb{R}$, has special subsets called intervals. An interval is a set containing all real numbers between two given numbers, which are called the endpoints.

Finite Intervals

There are four types of finite intervals:

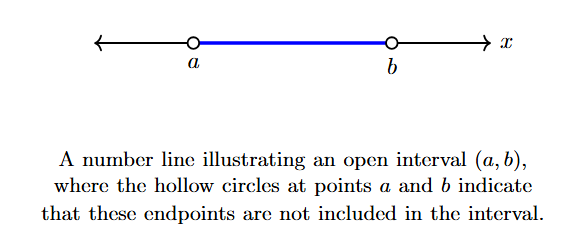

1. Open Interval

An interval that does not include its endpoints. It is denoted by $(a, b)$.

Set-builder form: $(a, b) = \{x : x \in \mathbb{R}, a < x < b\}$

Number line: Represented with hollow circles at the endpoints.

2. Closed Interval

An interval that does include its endpoints. It is denoted by $[a, b]$.

Set-builder form: $[a, b] = \{x : x \in \mathbb{R}, a \le x \le b\}$

Number line: Represented with filled circles at the endpoints.

![Closed Interval [a, b] Number line showing a closed interval from a to b with filled circles at both ends.](../../Mathematics/b5. Class 11th Concepts with Examples/Chapter 1 Images/4.png)

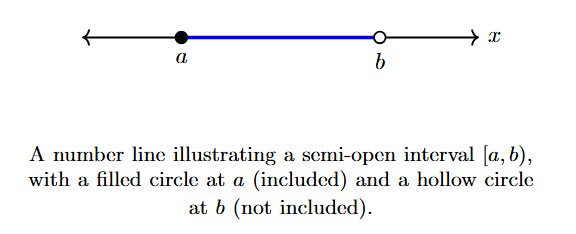

3. Semi-open or Semi-closed Intervals

These intervals include one endpoint but not the other.

(i) Closed on the left, open on the right: $[a, b)$

Set-builder form: $[a, b) = \{x : x \in \mathbb{R}, a \le x < b\}$

(ii) Open on the left, closed on the right: $(a, b]$

Set-builder form: $(a, b] = \{x : x \in \mathbb{R}, a < x \le b\}$

![Semi-open Interval (a, b] Number line showing an interval from a to b with a hollow circle at a and a filled circle at b.](../../Mathematics/b5. Class 11th Concepts with Examples/Chapter 1 Images/2.png)

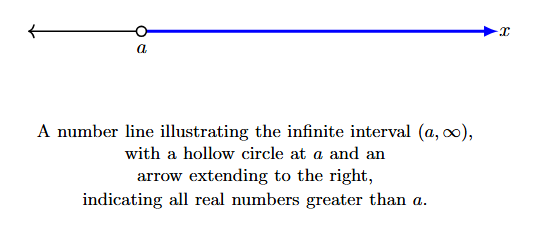

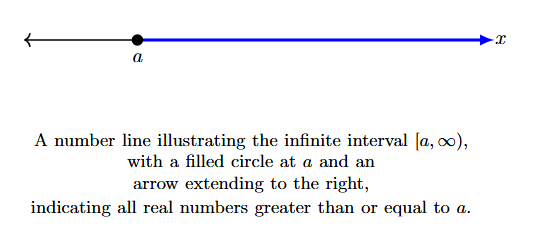

Infinite Intervals

Intervals can also be unbounded, extending to infinity ($\infty$) or negative infinity ($-\infty$). Note that $\infty$ and $-\infty$ are not real numbers, so the interval is always open at the infinity end (i.e., we always use a parenthesis for $\infty$ or $-\infty$).

1. $(a, \infty)$: The set of all real numbers greater than $a$.

Set-builder form: $\{x : x \in \mathbb{R}, x > a\}$

2. $[a, \infty)$: The set of all real numbers greater than or equal to $a$.

Set-builder form: $\{x : x \in \mathbb{R}, x \ge a\}$

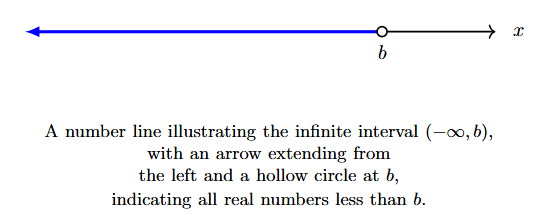

3. $(-\infty, b)$: The set of all real numbers less than $b$.

Set-builder form: $\{x : x \in \mathbb{R}, x < b\}$

4. $(-\infty, b]$: The set of all real numbers less than or equal to $b$.

Set-builder form: $\{x : x \in \mathbb{R}, x \le b\}$

![Infinite Interval (-∞, b] Number line with an arrow extending from negative infinity to a filled circle at 'b'.](../../Mathematics/b5. Class 11th Concepts with Examples/Chapter 1 Images/8.png)

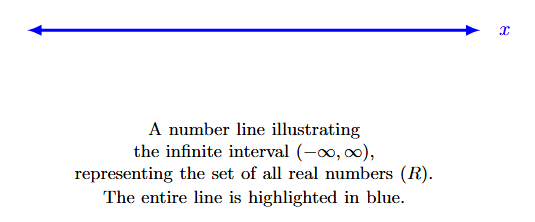

5. $(-\infty, \infty)$: The set of all real numbers, $\mathbb{R}$.

Set-builder form: $\{x : x \in \mathbb{R}\}$

Length of an Interval

The length of any finite interval (open, closed, or semi-open) with endpoints $a$ and $b$ is given by the difference between the endpoints: $b - a$.

Example: The length of the interval $[-3, 5]$ is $5 - (-3) = 5 + 3 = 8$. The length of $(-3, 5)$ is also 8.

2. Superset:

The concept of a superset is the inverse of the subset relationship.

If $A$ is a subset of $B$ ($A \subseteq B$), we say that $B$ is a superset of $A$. We write this as $B \supseteq A$. The symbol '$\supseteq$' means "is a superset of".

If $A$ is a proper subset of $B$ ($A \subsetneq B$), we say that $B$ is a proper superset of $A$. We write this as $B \supsetneq A$ or sometimes $B \supset A$. The symbol '$\supsetneq$' means "is a proper superset of".

For example, for the sets $A = \{1, 2\}$ and $B = \{1, 2, 3\}$, since $A \subsetneq B$, $B$ is a proper superset of $A$, written as $\{1, 2, 3\} \supsetneq \{1, 2\}$.

3. Universal Set:

In any particular context involving sets, we often work with elements that are all part of a larger, encompassing set.

This large set, which contains all the sets under consideration in a given problem, is called the Universal Set.

The universal set is typically denoted by the symbol $U$.

Sometimes, other symbols like $\Omega$ (Omega) or $S$ (for Sample Space, especially in Probability theory) are also used.

It is crucial to understand that the universal set is not fixed. It depends entirely on the specific problem or context you are working in.

Examples of Universal Sets

1. If we are discussing sets related to students in a school (e.g., the set of students in Class 11, the set of students in the basketball team), then a suitable universal set $U$ would be the set of all students in that school.

2. If we are discussing sets of numbers, like the set of even integers or the set of prime numbers, the universal set can vary based on the context.

- It could be the set of all integers, $\mathbb{Z}$.

- It could be the set of all rational numbers, $\mathbb{Q}$.

- It could be the set of all real numbers, $\mathbb{R}$.

- It could even be the set of all complex numbers, $\mathbb{C}$.

3. Suppose we are given sets $A=\{1, 2\}$ and $B=\{2, 3, 4\}$. If the context implies we are only dealing with small positive integers, a possible universal set could be $U=\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$. Alternatively, the set of all natural numbers, $\mathbb{N}$, could also be the universal set. The choice of the universal set defines the boundaries for the problem.

4. Power Set:

The Power Set of a given set $A$ is the collection or set of all possible subsets of $A$.

Every power set includes the empty set ($\emptyset$) and the set $A$ itself as its elements.

The power set of a set $A$ is denoted by $P(A)$ or sometimes by the symbol $2^A$.

Symbolic Definition of Power Set

Formally, the power set $P(A)$ is defined as the set of all sets $S$ such that $S$ is a subset of $A$.

$P(A) = \{ S : S \subseteq A \}$

This definition means that an element $S$ belongs to the power set $P(A)$ if and only if $S$ is a subset of $A$. It is important to remember that the elements of a power set are themselves sets.

Examples of Power Sets

Example 1. Find the power set of $A = \{a, b\}$.

Answer:

To find the power set of $A$, we need to list all of its possible subsets.

Subsets with 0 elements: $\emptyset$

Subsets with 1 element: $\{a\}$, $\{b\}$

Subsets with 2 elements: $\{a, b\}$

The power set $P(A)$ is the set containing all of these subsets.

$P(A) = \{\emptyset, \{a\}, \{b\}, \{a, b\}\}$

Example 2. Find the power set of $B = \{1, 2, 3\}$.

Answer:

We list all possible subsets of $B$.

Subsets with 0 elements: $\emptyset$

Subsets with 1 element: $\{1\}$, $\{2\}$, $\{3\}$

Subsets with 2 elements: $\{1, 2\}$, $\{1, 3\}$, $\{2, 3\}$

Subsets with 3 elements: $\{1, 2, 3\}$

The power set $P(B)$ is the set containing all of these subsets.

$P(B) = \{\emptyset, \{1\}, \{2\}, \{3\}, \{1, 2\}, \{1, 3\}, \{2, 3\}, \{1, 2, 3\}\}$

Example 3. Find the power set of the empty set, $C = \emptyset$.

Answer:

The only subset of the empty set is the empty set itself. That is, $\emptyset \subseteq \emptyset$.

Therefore, the power set of the empty set contains only one element, which is the empty set.

$P(\emptyset) = \{\emptyset\}$

Note: $P(\emptyset)$ is not the empty set. It is a singleton set whose only element is the empty set.

Cardinality of a Power Set

The cardinality (or number of elements) of the power set of a finite set $A$ is determined by the cardinality of $A$.

If a set $A$ has $n$ elements, i.e., $n(A) = n$, then the number of elements in its power set, $n(P(A))$, is $2^n$.

The formula is:

$n(P(A)) = 2^{n(A)}$

Derivation of the formula $n(P(A)) = 2^{n(A)}$

This formula can be derived using different methods. Below are two common approaches.

Method 1: Using the Multiplication Principle (The Decision Method)

This method is intuitive and relies on the fundamental principle of counting.

Let $A$ be a finite set with $n$ distinct elements, say $A = \{e_1, e_2, \dots, e_n\}$.

To construct any subset of $A$, we must make a decision for each element in $A$: whether to include it in the subset or to exclude it.

- For the first element, $e_1$, we have 2 choices (include or exclude).

- For the second element, $e_2$, we again have 2 choices, independent of the choice for $e_1$.

- This pattern continues for all $n$ elements. For the last element, $e_n$, we have 2 choices.

Since we have a sequence of $n$ independent decisions, each of which can be made in 2 ways, the Multiplication Principle of Counting states that the total number of possible outcomes (which corresponds to the total number of subsets) is the product of the number of choices at each step.

Total number of subsets = (Choices for $e_1$) $\times$ (Choices for $e_2$) $\times \dots \times$ (Choices for $e_n$)

Total number of subsets = $\underbrace{2 \times 2 \times \dots \times 2}_{n \text{ times}}$

Total number of subsets = $2^n$

Since the power set $P(A)$ is the set of all these possible subsets, its cardinality is $2^n$. As $n = n(A)$, we have our formula:

$n(P(A)) = 2^{n(A)}$

Method 2: Proof by Mathematical Induction

This is a more formal and rigorous proof.

Let $S(n)$ be the statement: "A set with $n$ elements has $2^n$ subsets." We will prove this for all non-negative integers $n$ using induction.

1. Base Case:

Let $n=0$. A set with 0 elements is the empty set, $A = \emptyset$. The only subset of $\emptyset$ is $\emptyset$ itself. So, its power set is $P(A) = \{\emptyset\}$.

The number of subsets is $n(P(A)) = 1$.

Using the formula, for $n=0$, we get $2^0 = 1$.

Since the values match, the statement $S(0)$ is true.

2. Inductive Hypothesis:

Assume that the statement $S(k)$ is true for some non-negative integer $k$. That is, assume that any set with $k$ elements has exactly $2^k$ subsets.

3. Inductive Step:

We must prove that the statement $S(k+1)$ is also true. That is, a set with $k+1$ elements has $2^{k+1}$ subsets.

Let $B$ be a set with $k+1$ elements. We can write it as $B = \{e_1, e_2, \dots, e_k, e_{k+1}\}$.

Now, consider the subset of $B$ formed by removing the last element: $A = \{e_1, e_2, \dots, e_k\}$. The set $A$ has $k$ elements.

By our inductive hypothesis, the number of subsets of $A$ is $2^k$.

Now, we can classify all the subsets of the larger set $B$ into two disjoint categories:

- Case (a): Subsets of $B$ that DO NOT contain the element $e_{k+1}$.

These subsets are formed using only elements from $A = \{e_1, \dots, e_k\}$. Therefore, these are precisely the subsets of $A$. By the inductive hypothesis, there are $2^k$ such subsets. - Case (b): Subsets of $B$ that DO contain the element $e_{k+1}$.

Each of these subsets can be formed by taking a subset of $A$ and then adding the element $e_{k+1}$ to it. Since there are $2^k$ subsets of $A$, we can form exactly $2^k$ new, unique subsets of $B$ by including $e_{k+1}$ in each of them.

The total number of subsets of $B$ is the sum of the counts from these two cases:

Total subsets of $B$ = (Subsets without $e_{k+1}$) + (Subsets with $e_{k+1}$)

Total subsets of $B$ = $2^k + 2^k = 2 \cdot (2^k) = 2^{k+1}$

This result shows that a set with $k+1$ elements has $2^{k+1}$ subsets. Thus, the statement $S(k+1)$ is true.

4. Conclusion:

Since the base case is true and the inductive step has been proven, by the principle of mathematical induction, the statement $S(n)$ is true for all non-negative integers $n$.

Example 1. Find the number of subsets and proper subsets of the set $A = \{a, b, c, d\}$.

Answer:

The given set is $A = \{a, b, c, d\}$.

First, we find the number of elements in set $A$. The distinct elements are a, b, c, and d. There are 4 elements.

The number of elements in $A$ is $n(A) = 4$.

The number of subsets of a set with $n$ elements is $2^n$. Using the formula $n(P(A)) = 2^{n(A)}$:

Number of subsets of $A = 2^{n(A)} = 2^4$

Calculating $2^4$: $2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 = 16$.

So, the number of subsets of $A$ is 16.

A proper subset is a subset that is not equal to the original set. For any non-empty set, the set itself is one of its subsets, but it is not a proper subset. The only subset that is not proper is the set $A$ itself.

Therefore, the number of proper subsets is the total number of subsets minus 1 (for the set $A$ itself).

Number of proper subsets of $A = (\text{Number of subsets of } A) - 1$

= $16 - 1 = 15$

Thus, set $A$ has 16 subsets and 15 proper subsets.

Venn Diagrams

Venn diagrams are visual representations used to illustrate the relationships and logical operations between sets.

They offer a simple and intuitive method for understanding complex concepts in set theory.

These diagrams were introduced by the British logician and philosopher John Venn in the 1880s.

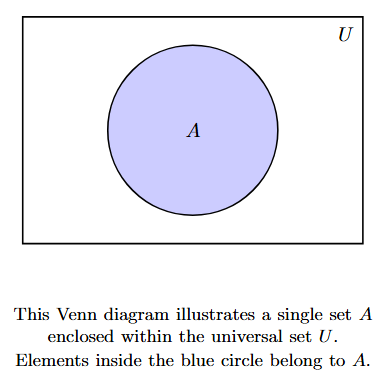

In a Venn diagram, the universal set ($U$) is typically represented by a rectangle.

This rectangle encloses all the elements relevant to the specific problem or context.

Subsets of the universal set are usually represented by closed curves, most often circles, drawn inside the rectangle.

The region inside a circle represents the elements belonging to that set.

The region outside the circle but inside the rectangle represents elements that are part of the universal set but not part of that specific set.

Representation of Sets and Relations using Venn Diagrams:

1. Single Set within Universal Set:

To represent a single set $A$ within a universal set $U$, we draw a rectangle for $U$ and a circle inside it for $A$.

In this diagram, the rectangle represents the universal set $U$, and the circle represents set $A$.

The area within the circle corresponds to the elements of set $A$.

The area outside the circle but inside the rectangle represents the elements that are in $U$ but not in $A$. This region is known as the complement of $A$, denoted as $A'$ or $A^c$.

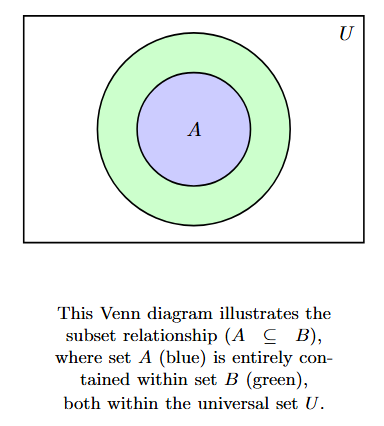

2. Subset Relationship:

When one set is a subset of another (e.g., $A \subseteq B$), it means every element of set $A$ is also an element of set $B$.

This relationship is shown in a Venn diagram by drawing the circle for set $A$ completely inside the circle for set $B$. Both circles are contained within the universal set $U$.

This diagram clearly illustrates the relationship $A \subseteq B$.

If $A$ is a proper subset of $B$ ($A \subsetneq B$), the circle for $A$ is strictly smaller and inside $B$. If $A = B$, the two circles would be identical and overlap perfectly.

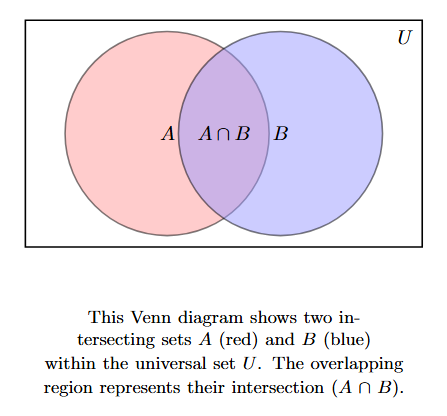

3. Two Intersecting Sets:

If two sets $A$ and $B$ have some elements in common, they are called intersecting sets.

In a Venn diagram, this is represented by two overlapping circles. The overlapping region represents the elements that are common to both set $A$ and set $B$.

This common region is known as the intersection of the sets, denoted by $A \cap B$.

This representation is often considered the general case for two sets, as it can visually accommodate all relationships (disjoint, subset, or intersecting).

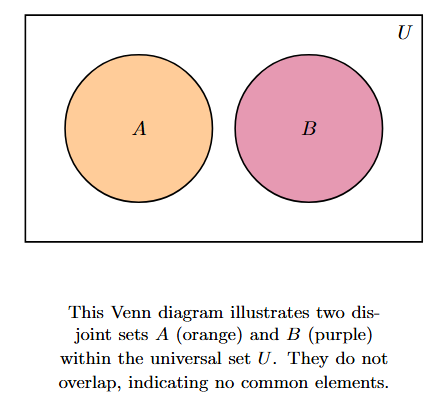

4. Disjoint Sets:

If two sets $A$ and $B$ have no elements in common, they are called disjoint sets.

Mathematically, this means their intersection is the empty set, i.e., $A \cap B = \emptyset$.

In a Venn diagram, disjoint sets are represented by two separate, non-overlapping circles drawn within the universal set rectangle.

This diagram clearly shows that there are no elements that belong to both set $A$ and set $B$ simultaneously.

Venn diagrams are an invaluable tool for visualizing relationships between sets. They are especially helpful for understanding set operations like union, intersection, and complement, and for verifying the properties of these operations.

Operations on Sets

Just as we perform fundamental operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division on numbers, we can also perform operations on sets to combine or relate them to form new sets. The basic operations on sets are Union, Intersection, Difference, and Complement. Another related operation is Symmetric Difference.

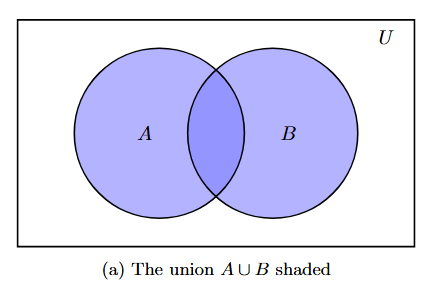

1. Union of Sets:

The Union of two sets, say $A$ and $B$, is a set that contains all the elements that are in set $A$, or in set $B$, or in both sets. Essentially, it is the collection of all distinct elements from both sets combined.

The union of sets $A$ and $B$ is denoted by the symbol '$\cup$'. We write it as $A \cup B$.

Symbolic Definition:

The union of $A$ and $B$ can be defined using set-builder notation as:

$A \cup B = \{ x : x \in A \text{ or } x \in B \}$

This reads as "the set of all elements $x$ such that $x$ is an element of $A$ or $x$ is an element of $B$ (or both)". The use of "or" in mathematics is inclusive, meaning it includes the case where $x$ is in both sets.

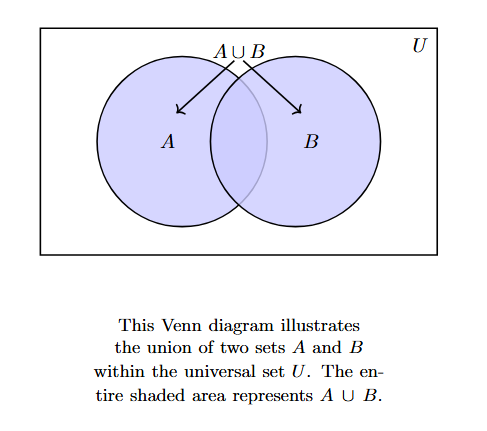

Venn Diagram Representation:

In a Venn diagram, the union of two sets $A$ and $B$ within a universal set $U$ is represented by shading the entire area covered by both circles $A$ and $B$.

The shaded region in the diagram shows the elements that are in $A$ or $B$ or both, which constitutes $A \cup B$.

Examples:

Let's illustrate the union operation with some examples:

1. If $A = \{1, 2, 3\}$ and $B = \{3, 4, 5\}$.

The elements in $A$ are 1, 2, 3. The elements in $B$ are 3, 4, 5. The union includes all distinct elements from both sets: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Note that the element 3, which is common to both sets, is listed only once in the union set.

$A \cup B = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$

2. If $P = \{a, e, i, o, u\}$ and $Q = \{a, b, c, d, e\}$.

The elements in $P$ are a, e, i, o, u. The elements in $Q$ are a, b, c, d, e. The union is the set of all distinct elements from both sets.

$P \cup Q = \{a, e, i, o, u, b, c, d\}$

Often, elements are listed in some order (like alphabetical order): $\{a, b, c, d, e, i, o, u\}$.

3. If $X = \{1, 2, 3\}$ and $Y = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$.

Notice here that $X$ is a subset of $Y$ ($X \subseteq Y$). When we form the union of $X$ and $Y$, we combine all elements. The elements of $X$ are already included in $Y$. So, the union will simply be the set $Y$.

$X \cup Y = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\} = Y$

This illustrates a general property: If $A \subseteq B$, then $A \cup B = B$.

Properties of Union:

The union operation satisfies several important properties:

(i) Commutative Law: The order of the sets does not matter in union. For any two sets $A$ and $B$, $A \cup B = B \cup A$.

(ii) Associative Law: When taking the union of three or more sets, the grouping does not affect the result. For any three sets $A$, $B$, and $C$, $(A \cup B) \cup C = A \cup (B \cup C)$. This allows us to write $A \cup B \cup C$ without ambiguity.

(iii) Identity Law (Law of $\emptyset$): The union of any set $A$ with the empty set $\emptyset$ is the set $A$ itself. $\emptyset$ acts as the identity element for the union operation.

$A \cup \emptyset = A$

(iv) Idempotent Law: The union of a set with itself is the set itself.

$A \cup A = A$

(v) Law of Universal Set: The union of any set $A$ with the universal set $U$ is the universal set $U$.

$A \cup U = U$

2. Intersection of Sets:

The Intersection of two sets, say $A$ and $B$, is the set that contains only those elements that are common to both set $A$ and set $B$. An element must be a member of *both* sets to be in the intersection.

The intersection of sets $A$ and $B$ is denoted by the symbol '$\cap$'. We write it as $A \cap B$.

Symbolic Definition:

The intersection of $A$ and $B$ can be defined using set-builder notation as:

$A \cap B = \{ x : x \in A \text{ and } x \in B \}$

This reads as "the set of all elements $x$ such that $x$ is an element of $A$ and $x$ is an element of $B$". The use of "and" signifies that the element must satisfy both conditions simultaneously.

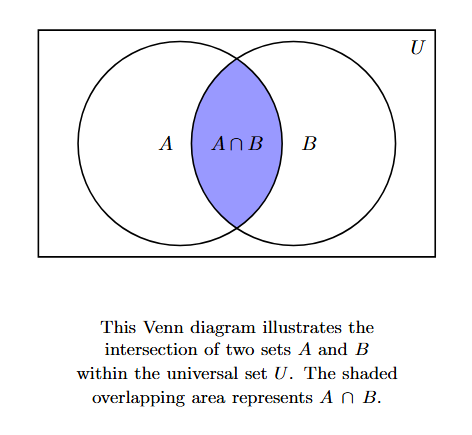

Venn Diagram Representation:

In a Venn diagram, the intersection of two sets $A$ and $B$ is represented by the overlapping region of the circles representing $A$ and $B$.

The shaded region represents the elements that are present in both $A$ and $B$, which is $A \cap B$.

Examples:

Let's illustrate the intersection operation with some examples:

1. If $A = \{1, 2, 3, 4\}$ and $B = \{3, 4, 5, 6\}$.

The elements that are present in both $A$ and $B$ are 3 and 4.

$A \cap B = \{3, 4\}$

2. If $P = \{a, b, c\}$ and $Q = \{d, e, f\}$.

Do these sets have any elements in common? No. There is no element that belongs to both $P$ and $Q$. Therefore, their intersection is the empty set.

$P \cap Q = \emptyset$

Sets like $P$ and $Q$ with no common elements are called disjoint sets (as discussed in the previous section and illustrated with a Venn diagram there).

3. If $X = \{1, 2, 3\}$ and $Y = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$.

Again, notice that $X \subseteq Y$. The elements common to both $X$ and $Y$ are the elements of $X$ itself (1, 2, 3).

$X \cap Y = \{1, 2, 3\} = X$

This illustrates a general property: If $A \subseteq B$, then $A \cap B = A$.

Properties of Intersection:

The intersection operation satisfies several important properties:

(i) Commutative Law: The order of the sets does not matter in intersection. For any two sets $A$ and $B$, $A \cap B = B \cap A$.

(ii) Associative Law: When taking the intersection of three or more sets, the grouping does not affect the result. For any three sets $A$, $B$, and $C$, $(A \cap B) \cap C = A \cap (B \cap C)$. This allows us to write $A \cap B \cap C$ without ambiguity.

(iii) Identity Law (Law of $U$): The intersection of any set $A$ with the universal set $U$ is the set $A$ itself. $U$ acts as the identity element for the intersection operation in a specific way (it's the largest possible intersection).

$A \cap U = A$

(iv) Idempotent Law: The intersection of a set with itself is the set itself.

$A \cap A = A$

(v) Law of Empty Set: The intersection of any set $A$ with the empty set $\emptyset$ is the empty set.

$A \cap \emptyset = \emptyset$

(vi) Distributive Laws: These laws describe how union and intersection interact when combined.

(a) Intersection distributes over Union: The intersection of a set $A$ with the union of sets $B$ and $C$ is equal to the union of the intersection of $A$ with $B$ and the intersection of $A$ with $C$.

$A \cap (B \cup C) = (A \cap B) \cup (A \cap C)$

(b) Union distributes over Intersection: The union of a set $A$ with the intersection of sets $B$ and $C$ is equal to the intersection of the union of $A$ with $B$ and the union of $A$ with $C$.

$A \cup (B \cap C) = (A \cup B) \cap (A \cup C)$

3. Difference of Sets:

The Difference between two sets $A$ and $B$, denoted by $A - B$ or $A \setminus B$, is the set of all elements that are in set $A$ but are *not* in set $B$. It represents the elements that are unique to $A$ relative to $B$.

Symbolic Definition:

The difference $A - B$ is defined as:

$A - B = \{ x : x \in A \text{ and } x \notin B \}$

Similarly, the difference $B - A$ is the set of elements that are in set $B$ but *not* in set $A$:

$B - A = \{ x : x \in B \text{ and } x \notin A \}$

In general, $A - B$ and $B - A$ are not equal.

Venn Diagram Representation:

In a Venn diagram, the difference $A - B$ is represented by the part of the circle for $A$ that does not overlap with the circle for $B$.

The shaded region represents $A - B$.

The difference $B - A$ is represented by the part of the circle for $B$ that does not overlap with the circle for $A$.

The shaded region represents $B - A$.

Examples:

1. If $A = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$ and $B = \{3, 5, 6, 7\}$.

To find $A - B$, we look for elements in $A$ that are not in $B$. Elements in $A$: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Elements in $B$: 3, 5, 6, 7. Elements in $A$ that are NOT in $B$: 1, 2, 4.

$A - B = \{1, 2, 4\}$

To find $B - A$, we look for elements in $B$ that are not in $A$. Elements in $B$: 3, 5, 6, 7. Elements in $A$: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Elements in $B$ that are NOT in $A$: 6, 7.

$B - A = \{6, 7\}$

Clearly, $A - B \neq B - A$ in this case.

2. If $\mathbb{R}$ is the set of real numbers and $\mathbb{Q}$ is the set of rational numbers.

The difference $\mathbb{R} - \mathbb{Q}$ is the set of elements that are in $\mathbb{R}$ but not in $\mathbb{Q}$. By definition, these are the irrational numbers.

$\mathbb{R} - \mathbb{Q} = \mathbb{T}$ (the set of irrational numbers)

Relationship to Complement:

The difference $A - B$ can also be expressed using the intersection and complement operations. If we consider $B'$ as the complement of $B$ relative to the universal set $U$, then $A - B$ is the set of elements that are in $A$ AND in the complement of $B$ (i.e., not in $B$).

$A - B = A \cap B'$

This identity is often useful in simplifying set expressions.

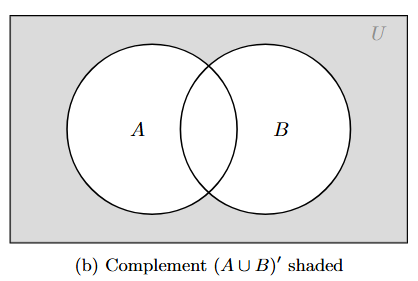

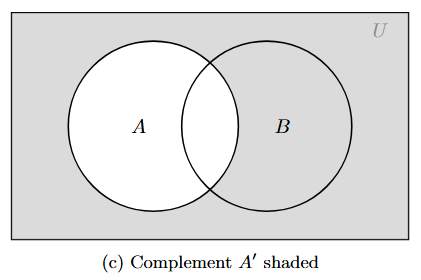

4. Complement of a Set:

The Complement of a set $A$, denoted by $A'$ or $A^c$ or $\overline{A}$, depends on the chosen universal set $U$. It is defined as the set of all elements in the universal set $U$ that are not in set $A$.

Symbolic Definition:

The complement of $A$ (with respect to $U$) is defined as:

$A' = \{ x : x \in U \text{ and } x \notin A \}$

This is equivalent to the difference between the universal set and set $A$:

$A' = U - A$

Venn Diagram Representation:

In a Venn diagram, the complement of set $A$ is represented by the region inside the universal set rectangle but outside the circle for $A$.

The shaded region represents $A'$.

Examples:

Let's see some examples of finding the complement of a set:

1. If $U = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7\}$ and $A = \{1, 3, 5\}$.

The elements in $U$ that are not in $A$ are 2, 4, 6, and 7.

$A' = \{2, 4, 6, 7\}$

2. If $U = \mathbb{R}$ (the set of all real numbers) and $\mathbb{Q}$ is the set of rational numbers.

The complement of $\mathbb{Q}$ with respect to $\mathbb{R}$ is the set of real numbers that are not rational. These are the irrational numbers.

$\mathbb{Q}' = \mathbb{R} - \mathbb{Q} = \mathbb{T}$ (the set of irrational numbers)

3. If $U$ is the set of all students in a school, and $G$ is the set of all girls in the school.

Assuming the school only has boys and girls, the complement of the set of girls would be the set of all students in the school who are not girls, which are the boys.

$G' = \text{Set of all boys in the school}$

Properties of Complement:

Let $A$ and $B$ be subsets of the universal set $U$. The following properties hold for the complement operation:

(i) Complement Laws:

(a) The union of a set and its complement is the universal set.

$A \cup A' = U$

(b) The intersection of a set and its complement is the empty set.

$A \cap A' = \emptyset$

(ii) De Morgan's Laws: These are two fundamental laws that relate the complement of unions and intersections to the complements of the individual sets.

(a) The complement of the union of two sets is the intersection of their complements.

$(A \cup B)' = A' \cap B'$

(b) The complement of the intersection of two sets is the union of their complements.

$(A \cap B)' = A' \cup B'$

(iii) Double Complementation Law (Involution Law): Taking the complement of the complement of a set returns the original set.

$(A')' = A$

(iv) Complement of Empty Set: The complement of the empty set is the universal set.

$\emptyset' = U$

(v) Complement of Universal Set: The complement of the universal set is the empty set.

$U' = \emptyset$

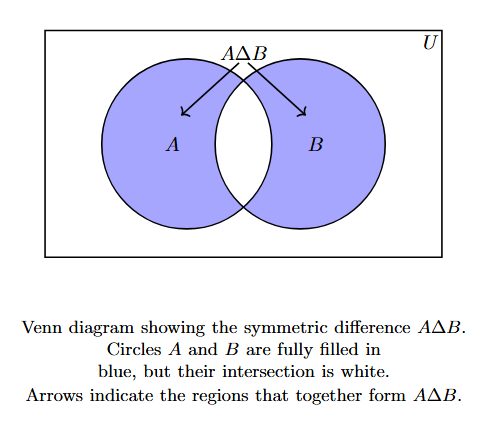

5. Symmetric Difference:

The Symmetric Difference of two sets $A$ and $B$ is the set of elements that are in either $A$ or $B$, but not in their intersection. It consists of elements that are in $A$ only or in $B$ only.

The symmetric difference of $A$ and $B$ is denoted by $A \Delta B$ or $A \ominus B$.

Symbolic Definition:

The symmetric difference can be defined in a couple of equivalent ways:

$A \Delta B = (A - B) \cup (B - A)$

This definition says it's the union of the elements unique to $A$ and the elements unique to $B$.

Equivalently, it can be defined as the elements in the union of $A$ and $B$ excluding the elements in their intersection:

$A \Delta B = (A \cup B) - (A \cap B)$

Venn Diagram Representation:

In a Venn diagram, the symmetric difference $A \Delta B$ is represented by shading the parts of circles $A$ and $B$ that do not overlap.

The shaded regions represent the elements that are in $A$ only ($A-B$) or in $B$ only ($B-A$), which together form $A \Delta B$.

Example:

Let's find the symmetric difference of the sets $A = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$ and $B = \{3, 5, 6, 7\}$.

Using the definition $A \Delta B = (A - B) \cup (B - A)$:

First, find $A - B$: Elements in $A$ but not in $B$. As calculated before, $A - B = \{1, 2, 4\}$.

Next, find $B - A$: Elements in $B$ but not in $A$. As calculated before, $B - A = \{6, 7\}$.

Now, find the union of these two difference sets:

$A \Delta B = \{1, 2, 4\} \cup \{6, 7\} = \{1, 2, 4, 6, 7\}$

Using the equivalent definition $A \Delta B = (A \cup B) - (A \cap B)$:

First, find $A \cup B$: Elements in $A$ or $B$ or both. $A \cup B = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7\}$.

Next, find $A \cap B$: Elements common to both $A$ and $B$. $A \cap B = \{3, 5\}$.

Now, find the difference of the union and the intersection:

$A \Delta B = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7\} - \{3, 5\}$

Remove the elements 3 and 5 from the set $\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7\}$.

= $\{1, 2, 4, 6, 7\}$

Both methods yield the same result, confirming the definitions.

Some Basic Results about Cardinal Number

When dealing with finite sets, we can use formulas to determine the number of elements (cardinality) resulting from set operations like union, intersection, difference, and complement. These formulas are very useful in solving problems involving a finite number of elements in sets, often encountered in practical scenarios.

Formulas for Cardinality of Sets:

Let $A$ and $B$ be finite sets, and let $U$ be the finite universal set containing $A$ and $B$.

1. Cardinality of the Union of Two Sets:

The number of elements in the union of two finite sets $A$ and $B$, denoted by $n(A \cup B)$, is given by the formula:

$n(A \cup B) = n(A) + n(B) - n(A \cap B)$

... (1)

This formula accounts for elements that are counted twice when simply adding $n(A)$ and $n(B)$ – the elements in the intersection $A \cap B$. By subtracting $n(A \cap B)$, we ensure that the elements common to both sets are counted only once in the union.

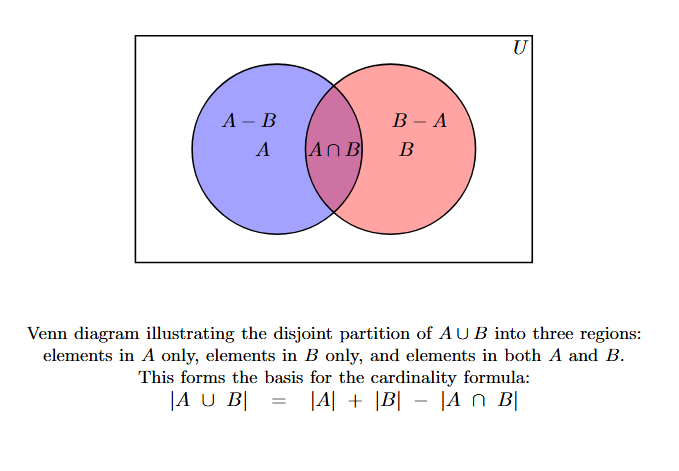

Derivation of Formula (1) using Venn Diagram:

Consider the Venn diagram representing two sets $A$ and $B$ within a universal set $U$. The diagram naturally partitions the elements into three disjoint regions:

- Elements in $A$ only (region $A - B$).

- Elements in $B$ only (region $B - A$).

- Elements in both $A$ and $B$ (region $A \cap B$).

The set $A$ is the union of the region "A only" and the region "A and B". These two regions are disjoint.

$A = (A - B) \cup (A \cap B)$

Since $(A-B)$ and $(A \cap B)$ are disjoint, the cardinality is the sum of their cardinalities:

$n(A) = n(A - B) + n(A \cap B)$

Similarly, the set $B$ is the union of the region "B only" and the region "A and B". These are also disjoint.

$B = (B - A) \cup (A \cap B)$

So,

$n(B) = n(B - A) + n(A \cap B)$

The union $A \cup B$ consists of the elements in the three disjoint regions: "A only", "B only", and "A and B".

$A \cup B = (A - B) \cup (B - A) \cup (A \cap B)$

Since these three sets are mutually disjoint, the cardinality of their union is the sum of their cardinalities:

$n(A \cup B) = n(A - B) + n(B - A) + n(A \cap B)$

From the equations for $n(A)$ and $n(B)$ above, we can express $n(A-B)$ and $n(B-A)$:

$n(A - B) = n(A) - n(A \cap B)$

$n(B - A) = n(B) - n(A \cap B)$

Substitute these expressions into the formula for $n(A \cup B)$:

$n(A \cup B) = (n(A) - n(A \cap B)) + (n(B) - n(A \cap B)) + n(A \cap B)$

Simplifying the right side by cancelling one $n(A \cap B)$ term:

$n(A \cup B) = n(A) + n(B) - n(A \cap B)$

[Simplified]

This completes the derivation of the formula.

2. Cardinality of Union for Disjoint Sets:

If sets $A$ and $B$ are disjoint, it means they have no elements in common. Symbolically, their intersection is the empty set: $A \cap B = \emptyset$. The number of elements in the empty set is 0, so $n(A \cap B) = 0$.

Substituting $n(A \cap B) = 0$ into the general formula (1):

$n(A \cup B) = n(A) + n(B) - 0$

This gives the formula for the union of two disjoint sets:

$n(A \cup B) = n(A) + n(B)$

... (2)

This is a straightforward result: if sets don't overlap, the total number of elements when they are combined is simply the sum of the number of elements in each set.

3. Cardinality of Difference of Sets:

As seen in the derivation of the union formula, the number of elements in the difference $A - B$ is related to the number of elements in $A$ and $A \cap B$. From the relationship $n(A) = n(A - B) + n(A \cap B)$, we can rearrange to find $n(A-B)$:

$n(A - B) = n(A) - n(A \cap B)$

... (3)

Similarly, the number of elements in $B - A$ is:

$n(B - A) = n(B) - n(A \cap B)$

... (4)

These formulas are useful when we need to find the number of elements that belong exclusively to one set but not the other.

4. Cardinality of Complement of a Set:

Let $U$ be a finite universal set and $A$ be a finite subset of $U$. The complement of $A$, denoted by $A'$, consists of all elements in $U$ that are not in $A$. By definition, set $A$ and its complement $A'$ are disjoint sets, and their union is the universal set ($A \cup A' = U$).

Using the formula for the union of disjoint sets (formula 2):

$n(A \cup A') = n(A) + n(A')$

Since $A \cup A' = U$, we have $n(A \cup A') = n(U)$. Substituting this into the equation:

$n(U) = n(A) + n(A')$

Rearranging this equation to solve for $n(A')$, we get the formula for the cardinality of the complement:

$n(A') = n(U) - n(A)$

... (5)

This formula tells us that the number of elements not in $A$ (but within $U$) is found by subtracting the number of elements in $A$ from the total number of elements in the universal set $U$.

5. Cardinality of Symmetric Difference:

The symmetric difference of two sets $A$ and $B$, $A \Delta B$, is defined as the union of the elements in $A$ only and the elements in $B$ only: $A \Delta B = (A - B) \cup (B - A)$. The sets $(A-B)$ and $(B-A)$ are disjoint.

Using the formula for the union of disjoint sets (formula 2):

$n(A \Delta B) = n(A - B) + n(B - A)$

Now, substitute the formulas for $n(A-B)$ (formula 3) and $n(B-A)$ (formula 4):

$n(A \Delta B) = (n(A) - n(A \cap B)) + (n(B) - n(A \cap B))$

Simplifying the expression:

$n(A \Delta B) = n(A) + n(B) - 2n(A \cap B)$

... (6)

Alternatively, we can use the definition $A \Delta B = (A \cup B) - (A \cap B)$. Since $A \cap B$ is a subset of $A \cup B$, we can use a variation of the difference formula ($n(X-Y) = n(X) - n(Y)$ when $Y \subseteq X$).

$n(A \Delta B) = n(A \cup B) - n(A \cap B)$

... (7)

Both formulas (6) and (7) are valid for the cardinality of the symmetric difference. Formula (7) is often derived from formula (1) by rearranging it as $n(A \cup B) = n(A) + n(B) - n(A \cap B)$, then using formula (6): $n(A \Delta B) = n(A) + n(B) $$ - 2n(A \cap B) $$ = (n(A) + n(B) $$ - n(A \cap B)) $$ - n(A \cap B) = $$ n(A \cup B) - n(A \cap B)$.

6. Cardinality of the Union of Three Sets:

For three finite sets $A$, $B$, and $C$, the number of elements in their union is given by a more complex formula:

$n(A \cup B \cup C) = n(A) + n(B) + n(C) - n(A \cap B) - n(B \cap C) - n(A \cap C) + n(A \cap B \cap C)$

... (8)

This formula extends the principle used for two sets. We sum the cardinalities of the individual sets, subtract the cardinalities of all pairwise intersections (because elements in these intersections are counted twice), and finally add back the cardinality of the intersection of all three sets (because elements in $A \cap B \cap C$ are initially counted three times in $n(A)+n(B)+n(C)$, then subtracted three times in $n(A \cap B)+n(B \cap C)+n(A \cap C)$, resulting in a net count of zero, so we must add them back once).

Derivation of Formula (8):

We can derive this formula using the formula for the union of two sets repeatedly. Let $X = A$ and $Y = B \cup C$. Using formula (1), we have:

$n(A \cup (B \cup C)) = n(A) + n(B \cup C) - n(A \cap (B \cup C))$

This is $n(A \cup B \cup C)$ on the left side. Now we need to find expressions for $n(B \cup C)$ and $n(A \cap (B \cup C))$.

Apply formula (1) to $n(B \cup C)$:

$n(B \cup C) = n(B) + n(C) - n(B \cap C)$

Now consider the term $n(A \cap (B \cup C))$. Using the distributive law for intersection over union, we know $A \cap (B \cup C) = (A \cap B) \cup (A \cap C)$. Apply formula (1) to the sets $(A \cap B)$ and $(A \cap C)$. Let $P = A \cap B$ and $Q = A \cap C$.

$n((A \cap B) \cup (A \cap C)) = n(A \cap B) + n(A \cap C) - n((A \cap B) \cap (A \cap C))$

The intersection $(A \cap B) \cap (A \cap C)$ consists of elements common to $A$, $B$, and $C$. This is the intersection of all three sets, $A \cap B \cap C$.

$n(A \cap (B \cup C)) = n(A \cap B) + n(A \cap C) - n(A \cap B \cap C)$

Now, substitute the expressions for $n(B \cup C)$ and $n(A \cap (B \cup C))$ back into the initial equation for $n(A \cup B \cup C)$:

$n(A \cup B \cup C) = n(A) + \underline{(n(B) + n(C) - n(B \cap C))} - \underline{(n(A \cap B) + n(A \cap C) - n(A \cap B \cap C))}$

Remove the brackets and simplify:

$n(A \cup B \cup C) = n(A) + n(B) + n(C) - n(B \cap C) - n(A \cap B) - n(A \cap C) + n(A \cap B \cap C)$

Rearranging the terms for clarity gives the standard formula:

$n(A \cup B \cup C) = n(A) + n(B) + n(C) - n(A \cap B) - n(A \cap C) - n(B \cap C) + n(A \cap B \cap C)$

[Final Formula (8)]

Special Case for Three Mutually Disjoint Sets:

If sets $A$, $B$, and $C$ are mutually disjoint, it means that the intersection of any pair of distinct sets is empty, and thus the intersection of all three is also empty. That is, $A \cap B = \emptyset$, $B \cap C = \emptyset$, $A \cap C = \emptyset$, and $A \cap B \cap C = \emptyset$.

In this case, the cardinalities of all intersection terms in formula (8) are 0:

$n(A \cup B \cup C) = n(A) + n(B) + n(C) - 0 - 0 - 0 + 0$

So, for mutually disjoint sets, the cardinality of their union is simply the sum of their individual cardinalities:

$n(A \cup B \cup C) = n(A) + n(B) + n(C)$

This principle can be extended to any number of mutually disjoint sets.

Practical Problems on Sets

The concepts and formulas related to set operations, particularly the cardinality of unions and intersections, are frequently applied to solve practical problems. These problems often involve analyzing data from surveys or scenarios where individuals or objects possess certain characteristics or fall into different categories. The formulas derived in the previous section provide a systematic way to tackle such problems.

Example 1. In a group of 400 people, 250 speak Hindi and 200 speak English. How many people can speak both Hindi and English? Assume that each person speaks at least one of the two languages.

Answer:

Let $H$ represent the set of people who speak Hindi.

Let $E$ represent the set of people who speak English.

Given:

The total number of people in the group is 400. Since everyone speaks at least one language, this group represents the union of those who speak Hindi or English.

$n(H \cup E) = 400$

(Total people in the group)

Number of people who speak Hindi:

$n(H) = 250$

(People speaking Hindi)

Number of people who speak English:

$n(E) = 200$

(People speaking English)

To Find:

We need to find the number of people who speak both Hindi and English. This corresponds to the number of elements in the intersection of the two sets, $n(H \cap E)$.

Find $n(H \cap E)$.

Solution:

We use the formula for the cardinality of the union of two finite sets (Formula 1 from Section I9):

$n(H \cup E) = n(H) + n(E) - n(H \cap E)$

Substitute the given values into the formula:

$400 = 250 + 200 - n(H \cap E)$

Combine the numbers on the right side:

$400 = 450 - n(H \cap E)$

Now, we want to isolate $n(H \cap E)$. Add $n(H \cap E)$ to both sides and subtract 400 from both sides:

$n(H \cap E) = 450 - 400$

Perform the subtraction:

$n(H \cap E) = 50$

Thus, the number of people who speak both Hindi and English is 50.

The final answer is $\textbf{50}$.

Example 2. In a committee, 50 people speak French, 20 speak Spanish and 10 speak both Spanish and French. How many speak at least one of these two languages?

Answer:

Let $F$ be the set of people who speak French.

Let $S$ be the set of people who speak Spanish.

Given:

Number of people who speak French:

$n(F) = 50$

(Given)

Number of people who speak Spanish:

$n(S) = 20$

(Given)

Number of people who speak both French and Spanish (the intersection):

$n(F \cap S) = 10$

(Given)

To Find:

We need to find the number of people who speak at least one of the two languages. This corresponds to the number of elements in the union of the two sets, $n(F \cup S)$.

Find $n(F \cup S)$.

Solution:

We use the formula for the cardinality of the union of two finite sets (Formula 1 from Section I9):

$n(F \cup S) = n(F) + n(S) - n(F \cap S)$

Substitute the given values into the formula:

$n(F \cup S) = 50 + 20 - 10$

Perform the addition and subtraction:

$n(F \cup S) = 70 - 10$

$n(F \cup S) = 60$

Thus, the number of people who speak at least one of the two languages is 60.

The final answer is $\textbf{60}$.

Example 3. In a survey of 700 students in a school, 180 study Economics, 250 study Mathematics, 200 study Statistics, 80 study Economics and Mathematics, 70 study Mathematics and Statistics, 50 study Economics and Statistics, and 30 study all three subjects. Find the number of students who study none of these three subjects.

Answer:

Let $U$ be the universal set of all students surveyed.

Let $E$ be the set of students studying Economics.

Let $M$ be the set of students studying Mathematics.

Let $S$ be the set of students studying Statistics.

Given:

$n(U) = 700$

(Total students surveyed)